CREATE TO FREE YOURSELVES

Abraham Lincoln and the History of Freeing Slaves in America

Georges Adeagbo installation

Chesterwood, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

July 29 - September 4, 2023

CREATE TO FREE YOURSELVES

Abraham Lincoln and the History of Freeing Slaves in America

Georges Adeagbo installation

Chesterwood, Stockbridge, Massachusetts

July 29 - September 4, 2023

Who is Georges Adéagbo?

“I am not an artist. I do not make art. I am just a messenger.”

- Georges Adéagbo

Despite claiming that he is not an artist, Georges Adéagbo is a strong and distinctive voice in contemporary art. Born in Cotonou, Benin, in 1942, Georges studied law in Côte d’Ivoire and business administration in France in the 1960s. He began his artistic career when he returned to Benin after his father’s death in 1971.

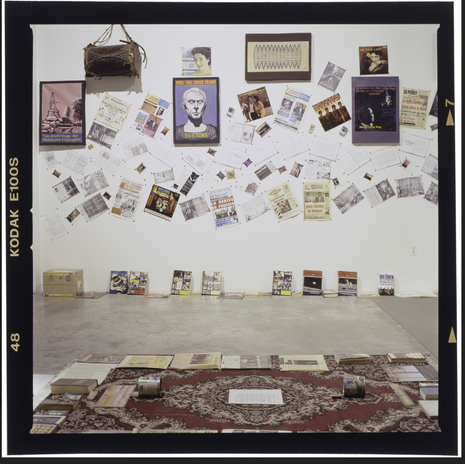

Georges’ practice is characterized by installations that combine objects, images, and text as a form of personal reflection. Through the process of creation, he explores the interrelationships between different objects and ideas in a continual circumambulation that raises new questions. Even the titles of Georges’s installations repeat key themes.

Stephan Köhler

By the 1990s, Georges had received widespread acclaim in the art world. In 1999, he was the first African artist to win the prestigious Jury Prize at the famed Venice Biennale for a one-day installation titled “The Story of the Lion.” Since then, he has moved between Benin, Germany, and world-class contemporary art museums that have commissioned his installations.

With a global following in the art world, Georges’s works have been installed or collected in Austria, Belgium, Benin, Brazil, Finland, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Norway, Senegal, Slovakia, South Africa, Spain, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, and the United States.

Although he recently turned 80 years old, Georges continues to explore and express his thoughts by writing and producing at least one temporary installation every day.

How does Georges Adéagbo create his installations?

“The Creator-God in creating us not to be slaves, how after the creation of God the Creator, did we become slaves?... my person is not a slave.”

- Georges Adéagbo

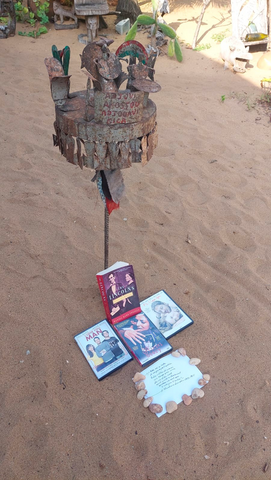

Each installation emerges from a fluid interaction between an idea, a place, and the many objects that Georges Adéagbo collects, assembles, and stores. Multiple visits to the site allow Georges to imagine how he might utilize different surfaces and spaces to communicate his ideas.

Prior to installing on site, Georges assembles many smaller, temporary installations to work through his ideas. Each provides him with the opportunity to try out ideas and explore the interrelationships between individual elements— books, newspapers, handwritten signs, found objects, and artworks created by a team of artists in Benin. In some cases, he also sketches a space with key elements of the installation as another form of preparation and rehearsal.

Stephan Köhler

Wherever Georges travels, he gathers objects for his personal collection, which he keeps in an archive at his studio in Benin. He collects materials that comment on, relate to, or amplify an idea or a site’s history or function. Each installation juxtaposes objects from the archive and the combinations frequently give rise to surprising implications.

Georges routinely takes objects from one place and installs them elsewhere but he always thinks

about the specificity of a site and establishes a network of associations between it and the objects in the installation.

For example, Georges has contrasted ancestral masquerades with images of an American ancestral figure to highlight a shared tradition of veneration that links Benin and the United States. While the formal aspects of these figures are quite different, they play a similar function connecting the past to the present, keeping the values and actions of those who have gone before present to the living.

Below you can watch the creation of one part of this installation over two weeks.

Why is Georges Adéagbo obsessed with Abraham Lincoln?

“The first of January 1863, President Abraham Lincoln published the Emancipation Proclamation which freed the slaves in the rebel states... the proclamation declared that the war was not waged for the sole purpose of saving the union but also to abolish slavery...”

- Georges Adéagbo

Many of Georges Adéagbo’s installations honor transformational historical figures. He considers them portraits. In issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Abraham Lincoln changed the trajectory of American history, and his actions inspired people around the world. In 2000, Georges created the first of his public “portraits” of Abraham Lincoln in an installation at the Museum of Modern Art in New York titled “Abraham--L’ami de Dieu” or “Abraham--Friend of God.”

Georges sees interrelationships between mythic stories and historical facts. He draws a parallel between the biblical Abraham, who gave his life to free the Jewish people, and Abraham Lincoln, who gave his life—in part—to free enslaved Americans.

Weaving together visual and textual narratives, Georges meditates on the concepts of sacrifice and freedom in this piece, linking the oppression of Jews in the Bible and the oppression of African people under colonialism and slavery in the United States. For Georges, sacrifice is an essential act that creates freedom.

How do you find freedom in your life? And where do you experience creativity most frequently or intensely?

Momo

How do others make sense of Georges Adéagbo’s installations?

“Experiencing the work of Georges Adéagbo is like traveling the map of another person’s mind. He shares with us what he reads and sees, inviting us to join him on a journey of association and thought. And the journeys are always thoughtful, provocative and visually stunning. ”

- Karen E. Milbourne, Senior Curator,

Smithsonian National Museum of African Art

Art historians and critics have all been enthralled by Georges Adéagbo’s unique installations. To help explain their importance, the critics have applied different lenses to these works.

Archiving: Georges collects, saves, and organizes diverse objects that reflect his vision of the past, and so his works can be seen as archives. Working in Benin and independently from any institution, he is decolonizing the archive from his unique position to create an alternative vision of past and present.

Simultaneity: Gathering artifacts from diverse places, displaying them across space, and sharing them at the same time, Georges identifies visual and conceptual commonalities and relationships between the characteristics that have too often been used to separate cultures. For him, everything exists together: African and Western art traditions; high and low culture; philosophy and kitsch.

Performance: Since Georges makes new, temporary installations every day, his works reflect a specific place and time—and comment upon it. He tests endless variations of different combinations. Each installation allows him to learn more about the objects and how they might fit into a larger piece.

How do these perspectives enrich your own experience of this installation?

How does Georges Adéagabo’s vision of Lincoln impact your own perspective?

“...Abraham Lincoln, the man who above all cared about reforging the union, not by force and repression, but by the warmth of his feelings and the generosity of his heart.”

- Georges Adéagbo

At President Lincoln’s Cottage, we share stories about Abraham Lincoln that show both the complexity of his character and the audacity of his leadership. Georges Adéagbo has created a three-dimensional portrait that fills the Cottage. It reflects the complexity of Abraham Lincoln’s life—and the many authors who have commented on him.

Lincoln carried a deep tension in his personality from an early age, and it was fully visible during his presidency. He was warm and generous, and he made some of the weightiest decisions in American history. He continuously consulted others but led from his deep, inner conviction. He was an active husband and father even as he was working to save the Union as president.

Within the installation, ancestral figures from Benin remind us that Lincoln is one of the critical figures from the past. And they raise questions about how Lincoln—and others from the past—remain with us in the present.

The installation ensconces Lincoln alongside other ancestors worthy of our veneration and respect. And it relativizes Lincoln by making clear that he is only one of many creative actors who made emancipation a reality.

Paintings show Lincoln in a wide range of situations. Whether giving a speech or posing in a formal portrait, the many images of the president reinforce the idea that he had many facets.

What other ideas does the installation bring up for you? How does Georges’s vision of Abraham Lincoln impact your understanding of him?

How do I make sense of so many individual objects?

Some people feel disoriented by Georges Adéagbo’s installations, but the density of objects invites you to enter a chain of associations. The artifacts provide you with the opportunity to discover and create connections involving motif, form, and theme. The link between the objects can produce meaningful associations across time and space. Even after hours of viewing, new relationships emerge.

Here are some places to start:

Look for the motif of the face. Where do you see faces in this room? How are they similar and different from one another? And what relationships do you see between them?

Choose a sculpture and look at it closely. Then find the other sculptures in this space and reflect on the relationships between them.

Focus on a single color and see how it moves your vision around the room.

Do you see a book that you know? What other texts has the artist included with it?

Now, start with the object that intrigues you the most and see where it leads your eyes and your reflections.

What do you create that expands freedom and improves your community?

“If my name ever goes into history, it will be for this act, and my whole soul is in it.”

- Abraham Lincoln on signing the

Emancipation Proclamation, 1863

Slavery was the defining issue of Abraham Lincoln’s presidency. Evolving his thinking and attitudes over time, Lincoln drafted the Emancipation Proclamation here in the Cottage in 1862, after many political consultations and many sleepless nights. When he signed the Proclamation in 1863, he said his whole soul was in it. In a speech in 1865, he suggested that formerly enslaved people should have the right to vote. And this led to his assassination.

What do you consider the defining issue of

our time?

How are you making a difference on that issue?

Into what acts do you put your whole soul?

Is there something that you are willing to give your life for?

Why is President Lincoln’s Cottage hosting Georges Adéagbo’s installation?

We preserve President Lincoln’s Cottage to connect people to the true spirit of the Lincolns, and we recognize that Abraham Lincoln means different things to different people. We also strive to be different from most other historical sites.

In 2021, Georges Adéagbo was hosted by the National Museum of African Art as part of a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship, which brings recognized artists to DC to use collections to inspire new creative works. He reviewed documents written by Lincoln and researched objects linked to Lincoln’s presidency and assassination. During his stay in Washington, he visited President Lincoln’s Cottage for the first time.

CREDITS

This project is a collaboration between President Lincoln’s Cottage at the Soldiers’ Home and the Smithsonian’s National Museum of African Art.

Project Team at President Lincoln's Cottage

Molly Cadwell, Project Manager

Joan Cummins, Program Coordinator

Callie Hawkins, Director of Programming

Jerry Jeffries. Special Events Manager

Rebecca Kilborne, Marketing and Communications Manager

Jeffrey Larry, Director of Preservation

Michael Atwood Mason, CEO and Executive Director

John Nembhard, Senior Museum Store Associate

Andrew Snow, Volunteer

Hannah Urrey, Director of Advancement

Cameron Walpole, Visitor Engagement Manager

Project Team at the National Museum of African Art Ngaire Blankenberg, Director

Michael Briggs, Web Manager

Ashley Jehle, Conservator

Gathoni Kamau, Acting Head of Visitor Engagement

John Lapiana, Senior Advisor

Bineta Mbengue, Social Media Manager

Karen E. Milbourne, Senior Curator

Kayla Redman, Programming Specialist

Brad Simpson, Photographer

Special thanks to the Howard University Gallery of Art at the Chadwick A. Boseman College of Fine Art